Learning about Color

My first experience in learning anything at all about color was in making color charts at the American Academy of Art. I was pretty bummed at the time and wanted to just move ahead to painting, but looking back now, it was a perfect introduction. In mixing up charts we learned about how paint handles, what happens when one color interacts with another, and how value is related to chroma. After this, we went on to painting monotone samples for a while, then with limited palettes, and finally full color, usually assignments ranging from still life painting, illustration, and figure painting. We always used gouache to paint, with the exception of specialized classes like oil painting or watercolor where we always painted from the model.

However, the real break through for me came from constant practice during my years as a background painter of environments and color scripts at Calabash Animation in Chicago combined with observational painting in my home studio and the Palette and Chisel Art League where Richard Schmid painted.

A Lucky Charms commercial pan background I painted in gouache on illustration board, approximately 3 ft. x 14" wide, around 1994

However, just working from what I learned in Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting was not enough. I also pored through books of other artists' work, studying paintings very, very closely. If I had no ideas on color schemes for seemingly mundane things like pavement or boring interior walls, I'd look at how Disney background painters were handling these subjects - usually with interesting lighting, chroma and contrast and learned how lighting and color can be an important compositional element in directing the eye. I combed through book stores and the library to find painters who were working from imagination; I practically memorized every inch of James Gurney's Dinotopia book for examples of great color.

"Lillies", 11x14, gouache on paper, 1992

But working from imagination alone, I believe, is not effective unless an artist works also from life. One tends to inform the other. During my years in Chicago, I regularly painted the still life, figures and portraits from life over at the Palette and Chisel, which helped me to develop a sense of how to mix paint, see color, simplify it, and apply it on canvas. I learned from Richard Schmid the principle of "cool light warm shadows, warm light cool shadows", something entirely new to me at the time. It was there that I learned how critical value relationships are to color, and how important it is to keep your color clean. Interestingly, I also learned from painting the figure and still life how it seems the majority of colors in any given subject seem to be more greyed down that I usually think at first, and how few really true high chroma colors are usually present.

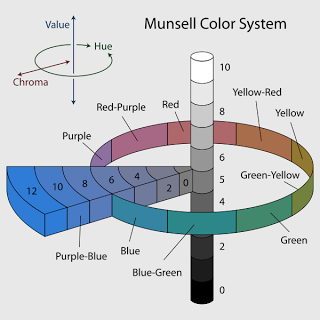

Later on, when I needed to switch to painting in Photoshop at work, the Munsell Color System in the program gave me a way to visualize how connected the relationships are between hue, chroma, and value.

After having these experiences, I believe that learning about color is not simply the study of one component like a color wheel or color charts. I believe it has to be a combination of methods plus a relentless pursuit in training your mind to see and translate color accurately. I am still learning and sharpening my color and values sense, and hope that by making another concerted push now in my life I might break through a plateau I've been experiencing the past few years. By documenting my experiences and writing down what I know plus reading new research and methods while also painting from life, I hope to make some improvements.

********************************

Learning to Mix Color

Color mixing is one skill in a set of skills that an artist needs to develop for painting in color.

As stated earlier, the first time I ever mixed color was my first year in art school where we mixed color charts. Later, I made much more extensive charts on a recommendation that Richard Schmid made during a lecture at the Palette and Chisel. When he eventually wrote his book, Alla Prima, he included the exact same advice where you can find it to make your own charts.

The purpose of making color charts is not so that you have "recipes" for mixing color. These charts are not meant to be short cuts, recipes or formulas for color. At the time I made these I did not know what each oil color did when combined with another in the palette I was using. When I had problems remembering what, for instance, cadmium yellow deep did when combined with terra rosa, looking at these charts helped guide me. When I needed to figure out what color I was looking at in a still life, if I referred to these charts, it helped my eye understand what it was seeing in terms of chroma and value - usually I would mix that color up and go from there by adding a bit of a third.

Going through the process of mixing colors for charts like this is important in learning many useful things about how to handle paint, how to physically mix it, apply it, manipulate it into values, observe what happens to it's temperature, and notice how important it is to keep it clean. Making charts like this is also useful when you add a new color to your base palette or for experimenting with a set of colors to find how it reacts with other colors in your palette.

********************************

Learning to Identify Color

Sometimes while I was first learning to paint, I used a small piece of white paper with holes punched in it. I would look through this piece of paper when I was stuck, aligning it with the color I was trying to identify. Very often I was surprised at what I found - a color that was either more grey, less saturated, and not at all what I thought it was. Often, I would mix up what I was seeing through the hole and put a small swatch up on the white piece of paper. I would keep doing this until I got the correct color.

Since I was using Photoshop to make this example, I placed the color wheel there too so you can see where the green of the water is placed within that particular hue.

Isolating colors using a white card punched with a hole puncher can help break down the symbols of what our mind "thinks" it sees into what is actually there. Over time, this simple tool helped me to discover just how saturated or non-saturated a color might be.

********************************

Tools to Understand Color

After sifting through multiple websites, I finally found two excellent sites that explain color and how an artist uses it. Just about everything an artist needs to know about the physical properties of color and light can be found on these two sites.

Other tools that help visualize and explain how color works are demonstrated in chart form. It is widely agreed within the realist painting community that the Munsell Color System is perhaps the most accurate way of understanding color and identifying it in context with other colors. The system identifies three terms: hue, chroma and value.

value: the black and white scale, brightness, how dark or light a subject is

hue: the local color of the subject

Another useful visualization of the Munsell Color System is the way that the program Adobe Photoshop represents it. Photoshop has an excellent color picker that brings up a color wheel. However, I prefer to use an enhanced extension called Magic Picker, an excellent color wheel for Photoshop used by many professional digital artists. If you have a copy of Photoshop, open up the program and experiment with painting swatches using the color wheel. Playing around with the sliders and adjusters really helped me see how color works using this system. This is the same chart depicted above, but represented differently.

Adobe published a technical guide regarding the Munsell Color System. You can find it HERE.

For further reading on the color wheel, read James Gurney's "The Color Wheel" series, Parts 1-7 on his blog, Gurneyjourney.blogspot.com. Gurney has a different but related approach culminating from his years of research on the color wheel. Excellent information, worth the read, including the comments.

Artist Graydon Parrish teaches a three week workshop in using the Munsell Color System at the Grand Central Art Academy in New York City each summer. The usefulness of learning the Munsell Color System is that it can help any artist identify any color, and use that color to depict anything he or she wishes. It is complex to understand at first, which requires some study and practice. I hope Graydon continues to teach - his classes are on the top of my list to attend!

Here is how Parrish describes the way he determines color in his paintings:

"What distinguishes my system is that I make strings of single chromas combined with single hues. I analyze what I am going to paint, find its notation, then mix up strings to cover the range. Reilly's method used cadmiums, way out of flesh range. A string of cad orange brought down with burnt umber/alizarin crimson shifts not only in value, but in hue and chroma as well, making it hard to predict. Reilly too recommended the addition of neutral greys to kill the chroma, but this causes the hues to shift as well. This is something Reilly never mentioned.

The above is just the beginning. One can analyze, then translate so many effects of nature into paint. I have a photo of a Bouguereau drawing where he had written the various colors of his model: green-grey, yellow-grey, rose-grey etc. With Munsell, the notations can be much closer. No more vague terms. (How much grey, for example, is in green-grey?) Its better to say 7.5 YR 6/3 or 7.5 R 5/4, for the average flesh and the ruddies. Then with mixing and planning, one can create an entire palette of Bouguereau flesh, for every change in value, and predict the rise and fall of chroma.

Likewise, Paris Hilton, could be studied and painted as well in all of her sun-tanned splendor. She is likely a chroma 5. When you then know where the chroma rises and where it falls, why some colors pull yellow in the lights and others don't, and how various transparent objects are more chromatic on the edges, then you have the beginning of an entire repertoire of visual phenomena from which to create." - quoted from the wetcanvas.com forums, HERE.

The above is just the beginning. One can analyze, then translate so many effects of nature into paint. I have a photo of a Bouguereau drawing where he had written the various colors of his model: green-grey, yellow-grey, rose-grey etc. With Munsell, the notations can be much closer. No more vague terms. (How much grey, for example, is in green-grey?) Its better to say 7.5 YR 6/3 or 7.5 R 5/4, for the average flesh and the ruddies. Then with mixing and planning, one can create an entire palette of Bouguereau flesh, for every change in value, and predict the rise and fall of chroma.

Likewise, Paris Hilton, could be studied and painted as well in all of her sun-tanned splendor. She is likely a chroma 5. When you then know where the chroma rises and where it falls, why some colors pull yellow in the lights and others don't, and how various transparent objects are more chromatic on the edges, then you have the beginning of an entire repertoire of visual phenomena from which to create." - quoted from the wetcanvas.com forums, HERE.

How Color Behaves in it's Environment

In addition to studying the Munsell system, learning how to mix and identify color, it is critical to also understand the principles of light and how color is affected by it. Matching color in any given subject is an important skill in developing the eye to see color correctly and helps to determine your palette and pigment choices. However, also understanding the reasons that make color appear a certain way in a particular situation is equally as important.

The very best books I can recommend are:

Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting

Andrew Loomis, Creative Illustration

James Gurney, Color and Light

Richard Schmid, Alla Prima

Here is a summary of some important points I learned from these books about how light and color work together:

- cool light produces warm shadows; warm light produces cool shadows. (Alla Prima)

- the most saturated color in a particular area is at the transition between the light side and the dark shadow and also at edges of objects. (Color and Light)

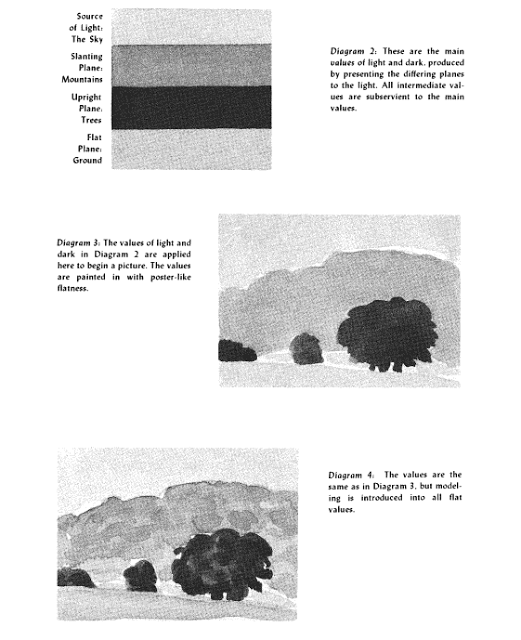

- Values in a landscape are often as depicted below, the source of the light, the sky, most often (even at night) being the lightest value in the landscape, the ground plane the second, slanting planes third, and upright planes usually the darkest. (Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting)

- Value is the most important factor in a painting, with hue and chroma coming next. If values are correct, hue and chroma will still be able to read. (Color and Light)

- a color will alter it's appearance depending upon the context of that color in the light or if other colors around it change. (Alla Prima, Color and Light)

- the limitations of pigments prevent us from depicting the wide range of luminosity in the world around us, so we must make adjustments in order to get across an approximation of what we see. (Alla Prima, Color and Light)

page 34, Carlson's Guide to Landscape Painting by John F. Carlson

In "Creative Illustration" by Andrew Loomis, he dedicates a chapter entirely to the great Howard Pyle. Loomis included this chapter in order to pass on directly, in print, information that was taken in note form during classes taught by Pyle regarding his general theory regarding light and color.

"All objects of nature are made visible to the sight by the light and of the sun shining upon them. The result is that by means of this we see the colors and textures of the various objects of nature.

From this it may be seen that color and texture are the property of light and that they do not enter the property of the shadow. For shadow is darkness and in the darkness there is neither form nor color.

Hence form and color belong distinctly to light. Shadow - as the object illuminated by the sun is more or less opaque, so when the light of the sun in obscured by that object, the shadow which results is more or less black and opaque, being illuminated only by the light reflected into it by surrounding objects.

By virtue of shadow all objects of nature assume form or shape, for if there were no shadow all would be a flat glare of light, color and texture...But when the shadow appears, the object takes form and shape.

If the edges of an object are rounded, then the edges of the shadow become softened; if the edges of an object are sharp, then the shadows is correspondingly acure. So, by means of the softness or sharpness of the solid object, is made manifest.

Hence, it would follow that the province of shadow is to produce form and shape, and that in itself it possesses no power of conveying an impression of color or texture."

-Howard Pyle, as quoted by Andrew Loomis, Creative Illustration, pg. 136